Excerpts from "The Snake Diary"

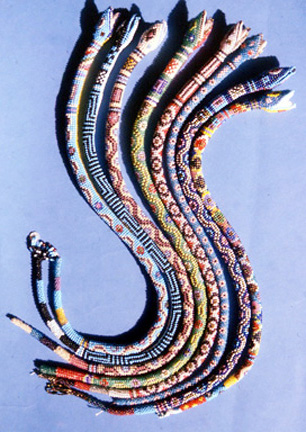

8 of the 49 beaded snakes from The Snake Project. Using a traditional Macedonian design format, I innovated colors and designs within basic design parameters.

I’m so excited. I fly into Pittsburgh to meet the people I’ll be working with next fall as curator at the folk art collection there. I’m only there for a day. They let me look at one or two boxes of folk costumes which I will be cataloguing for the museum. And there it is. A beaded snake, Macedonian, somehow identified as being used for dancing.

How did I know that it was a Macedonian dancing snake? Did the documentation say that? Did someone on staff say it? Did I make it up, or just assume it? I’m hazy on this point. And I don’t quite remember the pattern, either, except I think I do remember that it had squares. Yes, I remember squares, beaded and yellow. And somehow I remember thinking at the time that I had already seen another beaded Macedonian snake somewhere. Later, when I was actually working with the collection, I further remember looking for that snake, and either not being able to find it, or maybe it was already catalogued when I got there and there was so much to do that I really only had time to focus on the objects which had not been catalogued. Anyway, I did not get to look at it again before I left, a year and a half later. It started me on the path of looking for Macedonian beaded snakes. It took me years.

Do you know about Macedonian beaded snakes? I’ve been asking all kinds of people. Lots of no’s in Pirin (Bulgarian) Macedonia.

“Yes,” (1990) someone from a New York folk dance troupe told me. “Several people in our group have them. They got them when were in Jugoslavia.” I’m so excited, I’ll be able to borrow one to examine. But unfortunately, when I actually see it, it turns out to be an Albanian amulet necklace from Kosovo. I know, I got one myself in Kosovo, and have thoroughly quizzed the ladies who sell them. I can see how an American in a folk dance group would see it as a dancing snake, however.

“Yes,” my friend Jim tells me. He’s seen them in stores which sell folk art in Greece. 1993, he brings back a somewhat pathetic, bright orange, tourist beaded snake. “The good ones are all gone, they’ve all been sold, and they’re not a renewable resource.” Still, I’m thrilled to be able to have it to look at. To drape it around my hands, around doorknobs in my apartment. The head is done in a technique I can’t quite understand. I WANT to understand it. I thoroughly intend to find someone who knows how to make them. I want to learn. I really want to learn.

“Yes,” (1993) a Macedonian-Canadian woman tells me, “yes I have seem some in people’s houses.” I still haven’t been able to pursue this. I know that these are immigrants from Aegean (Greek) Macedonia. So…

Agia Germano (German) Greek Macedonia (summer 1994)I’m doing fieldwork in Bulgaria, and know my friend Jim is going to be in Greece. The phones in both countries are unreliable, particularly Bulgaria, but he finally gets through. We arrange to meet in Thessalonika, and then wind up going to a small village in northern Greek Macedonia.

Here we are, hanging out in the heat, waiting for siesta time to be over so we can get settled in a local guest house. I have my crocheted beading, working while Jim chats. Why not? I ask about beaded snakes, we’re in Macedonia. A man quietly disappears and comes back with a BEADED SNAKE! I’m so excited. I photograph it, hold it, take the pattern for the beading, examine it, ask about it. The head, however still eludes me. How do they do it? The body on this snake, too is in a technique I don’t quite understand.

That evening, we take a long walk and come across a dead snake in the road. Pay attention. The next day we get to another village where they also made beaded snakes, and although we try to meet someone who could explain how the heads are done technically, it doesn’t wind up being possible. The woman who comes to talk to us knows how to make the bodies, but does not herself know how to make the head. The head in particular is hard for me to understand. [And how did we get to that village? We were walking towards the lake, and a taxi appeared out of nowhere! I said to Jim “Let’s flag it down to get to the bead village.” We wouldn’t have been able to get here any other way.]

What are the snakes to these men? They are presents from their fiancees. The men clearly value them. An important clue comes from a Slavic speaking man, who calls them by the name of a specific snake, not the generic name. This particular snake, “smok” is considered in local folklore (and elsewhere in the Balkans) to live in every house as the master of the house. If you ever see this kind of snake in your house, you address it politely and formally as the master of the house, and never ever mistreat it. It guards the hearth. Later, a Bulgarian folklorist/colleague points out that giving the beaded snakes might therefore be seen as marriage magic. Household magic. Household protectors.

The DREAMAs I was working on my fourth snake, I had this dream. It became like an artistic vision for me. To see many snakes together, like the ones shown on the top of this page.

I’m in an old used book store, the hole-in-the-wall kind, not pretentious, with an owner who is clearly intimate with his collection, which appears disordered to anyone else. I notice that there are beautifully patterned snakes all over the place. I want to understand the patterns. I love how they all look together, winding in and out of things together. But all of a sudden, it occurs to me these are snakes; is it safe to mess with them? Of course, I realize, they’re ok because THEY’VE BEEN IN THE BOOKS! Great. I take out a pad, and start notating the patterns. I wake up, really upset because the notebook is still in the dream. Bit it’s still clear to me, many snakes, many colors, many patterns, and all of them together. I see them together in a bowl, on a platter, some sort of defined, transportable space.

Look at some examples of snakes from this project